If you’re reading this, chances are you’re already using containers in your development.

Or maybe just looking into it?

Either way, you’d like to learn about best practices for managing a Dockerized microservices development environment. That’s why today we’re going to look at Otto – the latest offering from Hashicorp to understand if and how it can help us container hackers to be more productive.

This will be the first in a series of posts in which we will be looking at many of the new tools trying to simplify microservice container-based development workflow. Others in this field include the likes of AZK.io, mantl.io, Nanobox, wercker, and of course, Codefresh.

Container-based development changes the way we work, creating new possibilities and presenting new challenges. Some things become significantly easier, but as always, complexity doesn’t disappear completely – it just moves lower down the stack. To provide maximum productivity and streamline the delivery flow from development and into production, complexity has to get hidden and abstracted away. The challenge is always the same: how to keep things simple without compromising flexibility. Ease of use comes at the expense of control.

Some history:

Before Docker exploded on the technology scene, Vagrant was the ultimate tool for building self-contained virtualized development environments. It allowed building and running software with all the needed tools and dependencies, without installing them on your development machine. Moreover it allowed you to closely match your production servers using exactly the same configuration management tools in development – be it Chef, Puppet, Ansible or Salt.

Vagrant did all that the way a good tool should: providing sensible defaults and giving the user a relatively easy to use configuration language for tweaking the details. Then Docker came out, bringing with it a new paradigm and quite a few questions for the die-hard Vagrant fans: Does Docker replace or complement Vagrant? Which one is a better option? And if the two are to play nicely together, what is the best way of combining them?

Vagrant certainly showed readiness to cooperate — version 1.6 introduced a built-in Docker virtualization provider. On the other hand, the Docker ecosystem is ever-growing, with Docker Machine and Docker Compose now providing a relatively easy way of managing your development environment (considering you’re only working with containers), comparable to what Vagrant does.

Enter Otto :

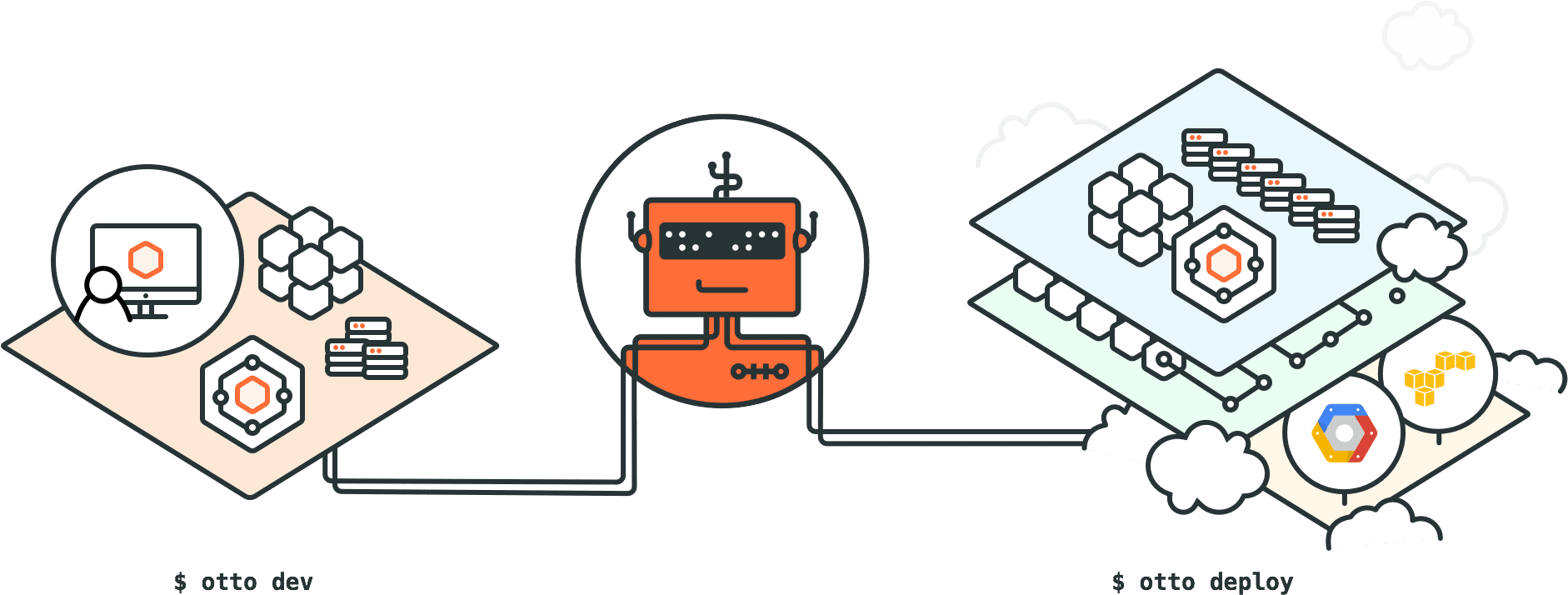

:

But this discussion is getting old as Hashicorp has recently started working on Otto, which is proclaimed to become the successor to Vagrant. The idea is exactly as discussed earlier: hiding the complexity of microservices architecture. Otto is focused on making the applications into first-class citizens, defining a usable application dependency management mechanism and bridging the gap between development and production by providing a unified deployment workflow.

As explained on the official site – Otto is:

- Built for microservices

- Focused on deployment

And specifically relevant to this post:

- Supports Docker out-of-the-box:

“Otto can use Docker to download and start dependencies for development to simplify microservices. Applications can be containerized automatically to make deployments easier without changing the developer workflow.” (from the otto site)

The official getting started guide shows how easy it is to get up and running with a Ruby application talking to a MongoDB backend. And guess what, MongoDB is actually getting executed in a container.

Let’s take a quick look at how Otto magic happens:

We’ll be using a simple Express.js web app with MongoDB as our example. The code source can be found on GitHub: https://github.com/codefresh-io/otto-example

$git clone https://github.com/codefresh-io/otto-example.git

The first step will obviously be downloading Otto. Get it here: https://www.ottoproject.io/downloads.html . There is a binary for Mac, Linux and Windows. (We’ll be running our example on a Mac, so if you’re on Windows – don’t forget to switch your slashes.)

The download is a single compiled go binary, which makes installation dead simple: just drop it somewhere in your path and you’re ready to run.

Otto is very good at automatically detecting our app type as long as we’re using a standard configuration and don’t need any external dependencies.

Once you have Otto installed, the initial configuration is as easy as changing into the application directory and running:

> otto compile

This is where Otto auto-detects our application type and defines all the needed defaults.

Looking at our application directory you’ll notice a .otto folder – this is where Otto stores all its data, and an .ottoid file which is the unique identifier for your app. The .ottoid file nas to be checked into version control, while .otto should not, therefore we’ve added it to our .gitignore.

The next step is actually creating our development environment. Back in our application directory we execute:

> otto dev

This will take significantly longer in the first execution, as this is the phase where Otto builds the virtual environment for our development. In fact, it uses Vagrant under the hood for provisioning local virtual infrastructure, saving the developer the hassle of writing Vagrant files manually. Everything is generated on the fly with VirtualBox being the default (and currently the only supported) virtualization provider.

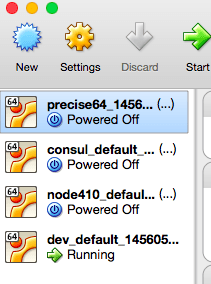

Once ‘otto dev’ returns a success status we will find that our VirtualBox got populated with 4 new VMs:

You’ll also notice that only one VM (the dev_default_…) is actually running, while the other 3 are turned off. This is because Otto works in ‘layers’, i.e., it creates base VM images when executed for the first time and then clones those when needed, to make subsequent executions very fast.

(Be careful about removing these VMs. Otto still doesn’t know how to recover if any of them go missing)

We’ll also see that besides Vagrant, there’s another Hashicorp tool under the hood, Consul, the smart service discovery and configuration system. One of the output lines when running ‘otto compile’ says:

==> default: [otto] Configuring consul service: ottofresh

– so Otto already gives us service discovery with zero configuration! Nice one.

Ok, so we got 4 VMs and service discovery, but what about Docker?

As I already mentioned – MongoDB is running inside a container. Let’s look at how this is configured:

Basic configuration file for each Otto application, or service, is the Appfile. This file is found at the root directory of our project and defines very little- our application name and one dependency that points to a subfolder ./monogdb:

application {

name = "ottofresh"

dependency {

source = "./mongodb"

}

}

Dependencies in Otto are other services that our main service depends on. Dependency source can also be a git repository url, but to make this example simpler and faster to run I’ve put the dependency definition in a subdirectory. In fact this ./monogdb directory only holds 2 files:

- an Appfile of its own

- and an .ottoid file

The .ottoid is a globally unique ID that is used to track the application across multiple deploys. It is required for the application to be used as a dependency. The Appfile looks as follows:

application {

name = "mongodb"

type = "docker-external"

}

customization {

image = "mongo:3.0"

run_args = "-p 27017:27017"

}

This defines that the ‘mongodb’ application is of type ‘docker-external’ and is to be executed in a container based on ‘mongo:3.0’ image with port mapping 27017:27017.

And this is exactly what happens.

If we go back to ‘otto dev’ command output we’ll see that it also says:

==> default: Running provisioner: docker...

default: Installing Docker onto machine…

==> default: Starting Docker containers... ==> default: -- Container: mongodb … ==> default: [otto] Configuring consul service: mongodb

Running ‘otto dev ssh’ inside the application directory brings us into the dev_default VM where ‘docker ps’ shows us that MongoDB is, in fact, running inside a container:

vagrant@precise64:/vagrant$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

9bc671e8cd68 mongo:3.0 "/entrypoint.sh mongo" 5 minutes ago Up 5 minutes 0.0.0.0:27017->27017/tcp mongodb

And – we can query Consul REST API to see all the services it has registered:

$ curl http://localhost:8500/v1/catalog/services {"consul":[],"ottofresh":[],"mongodb":[]}

Success! External dependencies can be defined to run in containers and registered/discovered in Consul with minimal configuration.

But what about our main application? What if we want to containerize it too?

After all, Otto promised us that “Applications can be containerized automatically to make deployments easier without changing the developer workflow.”

If you’ve cloned my example github repo – you’ll see that I’ve put a Dockerfile in it. Frankly, I was somehow hoping that Otto would see the Dockerfile and realize I want to dockerize my app. This still doesn’t happen automatically. Moreover,currently there’s no support for running your main app in a container. The only supported Docker app type is ‘docker-external’ – whereas a ready-made image is used to bring up a dependency service.

There are already a few change requests opened for this on Otto github, but it’s not clear when this is planned to be implemented.

This overview wouldn’t be complete without saying a few words about the way Otto extends the same workflow into production. Once we’re done with development and local testing, we can execute the ‘otto infra’ command that prepares the virtual infrastructure to deploy it to. Currently the only infra type supported is AWS, whereas Otto creates a VPC, subnets, proper routing tables, an Internet gateway, and more.

All this is done with Terraform – Hashicorp’s infrastructure configuration language/tool.

After the infra is set up we will run the ‘otto build’ command that uses Packer to wrap up our application.

Again, this currently only supports packaging an AWS AMI, but as we know Packer can also build Docker images (though it doesn’t use Dockerfiles for that) , so we can expect to see Docker build support in future Otto releases. In fact, it’s even promised on their site:

“In the very near future, the build step will build a container that is deployed using Nomad.

When this change comes, the build and deploy steps should become much faster, creating a much tighter feedback loop to deploying applications.”

Once our machine image is ready we type ‘otto deploy’ to deploy the newly built image to our infrastructure and voila – our service is up there in the cloud!

Summary:

- Otto provides quite a bit of magic, using all the other great tools from Hashicorp we’ve learned to use and love in the last years.

- Otto does the right thing: letting developers focus on applications and not on the infrastructure they run on.

- Otto is great when you’re doing things in a standard way, but it looks like it may be hard to tweak it to do something less mainstream, as all the Vagrant files, Packer and Terraform configs are getting generated automatically.

- Otto does provide great support for running dependency services in Docker containers based on ready-made images.

- As of now, it still doesn’t provide a way of building and testing a Docker image for the main application. But it looks like support for this is coming soon, so Otto is definitely a project to watch, based on Hashicorp’s impressive record of building great devops tools.

Make sure to subscribe to our blog – in the following posts we will compare Otto to additional projects focused on the same goal of making microservices development and deployment easy and efficient.